Davao Conference Workshop on Migration, Trafficking, Labour Exploitation and Centering the Human Rights of Migrants, Trafficked Persons, Domestic Workers, Other Affected Sectors

Davao City. Mindanao, Philippines

September 22-23, 2008

CONFERENCE STATEMENT

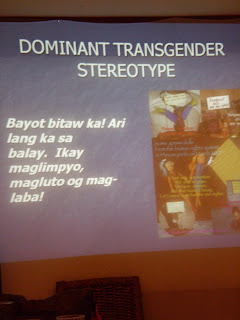

We, the representatives of civil society organizations, academic sector, self-organized groups of migrant returnees and community based-women, NGO anti-trafficking practitioners as well local government social welfare officers gathered here on September 22-23, 2008 at the Manor Hotel Davao, in Davao City, Mindanao Island, Philippines to discuss the current situation faced by migrants, trafficked persons, domestic workers, women in prostitution, transgendered sex workers and other sectors. The conference workshop is organized by the Buhay Foundation for Women and the Girl Child with support from the Global Alliance Against Traffic in Women (GAATW) and has invited participants not only from Davao City but also NGO practitioners from Cebu City, Baguio City and from Metro Manila area. For two full days, we shared experiences and practices, concepts and perspectives as well as engaged in dialogue and critical analysis, pinpointed the gaps and addressed challenges relevant to the themes of the conference.

We came to listen to the testimonies offered by women migrants who have returned, and are now involved in advocacy work in their own self-organized groups. We thank them for sharing their dreams which drove them to migrate, and the resulting situation they confronted. Thru their stories, we came to understand why women and individuals in general are moving/crossing borders to work and what is the journey they are making.

We have felt the need to affirm that migration is a human activity that needs to be respected. That throughout human history, people have been migrating. However, in contemporary times, human insecurities have been triggered by persecution, armed conflicts and the consequent forced displacement, survival and the push to search for better options in life, discrimination, underdevelopment, inequality, environmental destruction. These root causes also created the conditions for human rights violations to occur and vulnerabilities of people, especially women, to be exploited. More and more, we are witnessing intense migration flows of people from all walks of life and in the course of this phenomenon, we find numerous migrant workers put into situations of abuse and labour exploitation, some deceived by traffickers, or coerced into slavery like work conditions.

In the discussions during the conference workshop, we began to explore the significance of linkages between migration, trafficking, labour exploitation and human rights that the participants consider as important in order to address human rights violations in labour migration to destination countries and the vulnerabilities to trafficking and exploitation of certain sectors of migrants particularly women. We have seen the need to confront the reality of female migrant labour as gendered – with many Filipino women brought to work in informal sectors that are unregulated and unprotected.

In this regard, we, participants of the Davao Conference Workshop call for the responsibility of the states both in sending and destination countries towards the promotion of human rights and human security of the international migrants especially migrant workers, undocumented migrants, and the victims of organized crime thru trafficking in persons and the smuggling of migrants. We affirm that migrants must be able to exercise their fundamental human rights and benefit from minimum labor standards, and a minimum of socio-economic security in the countries of destination. At the same time, we call on the source/sending /departure countries like the Philippines to develop policies on economic development that set as its priority a sustainable economic strategy to enlarge the local labor markets rather than seek to export more labor to destination/receiving countries.

It has been eight years since the UN adopted the UN Convention on Transnational Organized Crime and its two supplementary protocols – the Protocol to Prevent Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, especially women and children and the Protocol on Migrant Smuggling. We express our deep concern that many states parties (particularly those in destination countries) have responded to the Trafficking Protocol by establishing legal frameworks aimed at restricting immigration and enforcing tighter border controls and which oftentimes result in restricting the movement of women who wish to migrate for work or in “profiling” certain types of women. In addition, anti-trafficking policies and initiatives have grown in number at the national and international level at an extraordinary rate since then. We share the current global concern expressed on the human rights impact of anti-trafficking measures through the 8-country research report of the Global Alliance Against Traffic in Women entitled “Collateral Damage: The Human Rights Impact of Anti-Trafficking Measures Worldwide” which findings, conclusions and recommendations were presented at this conference workshop in Davao City.

The Palermo protocol was signed and ratified by the Philippine government, and an Anti-trafficking in Persons Act had been passed in 2003 as a national law. In this conference workshop, we heard the report of the social work department officers of the Davao region and commended them on the dedication they showed on their work to prevent trafficking. They also reported the process of actively installing mechanisms such as the Davao Inter-agency Council Against Trafficking (IACAT) which engaged some NGOs in the work to prevent trafficking.

However, conference participants expressed their concern on some anti-trafficking measures that were implemented such as raids and rescues of women working in establishments deemed as “fronts” for prostitution. This practice seemed to have become “standard” anti-trafficking responses as gleaned from similar reports in some countries of South East Asia and South Asia. Serious concern were also expressed over the reported practice of some local and national-based anti-trafficking NGOs, who in cooperation with government agencies, were profiling unaccompanied young travelers below 15 years old and young women aged 15 to 18 as “potentially trafficked”. In the name of anti-trafficking campaigns such as “the war against trafficking” launched in August 2008 by NGOs supported by US government money, the youths and young women were held in halfway shelters near seaports, holding them for some 3 days or more, and virtually converting the shelters as temporary detention centers. It was discussed in the Davao conference human rights provisions of the Trafficking Protocol such as Article 2 which obligates States Parties to implement the Protocol with full respect for the human rights of trafficked persons and migrants whose rights are being affected by arbitrarily classifying certain types as “potentially trafficked”.

Speakers in the conference workshop have also raised questions and criticism on how one country has used its annual (Trafficking In Persons)TIP report and tier-ranking of countries anti-trafficking performance. It was reported that this has pressured several countries in Asia to institute measures and policies such as arbitrary raids and rescues, some of which have been documented as affecting negatively the human rights of migrant workers, women in the site of prostitution and other sectors.

In this regard, the participants call on the anti-trafficking NGO community in Davao City as well as in various cities and provinces of the Philippines to be aware of the human rights implications of some initiatives to end trafficking, whether by the government or of local/national NGOs, and to ensure that the human rights of migrant workers, trafficked persons and all others affected by anti-trafficking measures, are at the center of our work.

In addition, we urge civil society organizations to participate in the monitoring and review of the implementation of the Palermo protocol on human trafficking in the Philippines, as well as the national anti-trafficking law of 2003, and provide specific policy recommendations to respond to gaps and harmful practices seen.

We also urge the academic sector to support and be a partner in the efforts to generate evidence-based researches that can serve as inputs to policy making. There is need to provide evidence on the number of persons being trafficked, for what purposes, the patterns of trafficking and whether the human rights of the migrants and trafficked persons are protected or violated. Interviews and case studies of trafficking cases can enlighten us on the layered experiences and realities of the affected persons.

We wish to address the forthcoming meeting of government leaders such as the Global Forum on Migration and Development (GFMD) being held Oct. 27-30 this year, and the ASEAN Summit in Bangkok in December 2008 by drawing the attention of governments to the situation of millions of migrants around the world, and particularly in the ASEAN region, and to the need to take action and improve their situation by putting human rights protection of migrants as an important core agenda. Specifically, we urge the States to curb violations of migrant rights such as putting undocumented migrants in immigration detention centers.

We sincerely welcome the adoption of the ASEAN Declaration on the Protection and Promotion of the Rights of Migrant Workers in January 2007 and the establishment of the ASEAN Committee to Implement (ACI) the Declaration on the Protection and Promotion of the Rights of Migrant Workers in July 2007.

We recommend for a national and local campaign network to be set up to generate broad solidarity and concerted action as well as to address the challenge of advancing a movement in the country with a clear direction and message of centering the rights of Filipino migrant workers and trafficked persons that will ensure their voices and agency at the core of anti-trafficking policies, measures and practices.

And finally, because we are in the island of Mindanao, which is facing today an intensified armed conflict situation, we would like to express our deep concern to a growing number of migrants from among the Moro communities who are victims of displacement due eruption of armed hostilities between the military forces of the Philippine government and the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF). We support the clamor for an immediate cessation of hostilities, in particular, for the Philippine military to desist from further military offensives, and that it immediately pulls out its troops from the region, and return to the negotiating table. We also oppose the arming of civilians by the Philippine government and demand the immediate disbandment of militias and private armies. Lastly, we will share in the collective task of civil society organizations to undertake activities that will advance a just and peaceful solution to the 30-year conflict in Mindanao , one that respects the right of the Moro people for self-determination and provides a long lasting framework to the displacement and consequent migration flow of peoples from affected Moro communities.

Specific action points and proposals have been framed in the attached RECOMMENDATIONS to respond to the abuse and exploitation of migrant labour and the deepening of vulnerabilities of women and communities; to prevent trafficking, protect trafficked persons and others affected by anti-trafficking policies; and to prosecute traffickers and illegal recruiters and those in government involved in corruption activities. We hope that any campaign network or mechanism to be formed in the future will be tasked to realize the implementation of the attached recommendations that has come out from this conference workshop.

Recommendations to the Philippine Government

Policies and procedures for recruitment of migrant workers to work outside the country

In our work as NGOs and civil society organizations working closely with migrant workers, we have identified a number of important problems related to recruitment that need urgent solutions. We recognize that there is often a gap between the promises of the Government to follow international standards and the reality faced by the people who are seeking to migrate.

- A standard employment contract that contains sections that specify the core rights of migrant workers, and mechanisms to protect those rights. Each contract must also include a clear and detailed job description and relevant information on working and living conditions that that migrant worker will face in the receiving country.

- Enforce the law relating to the standard placement fee. Greater efforts should be made to create public awareness of the standard fee, and to increase monitoring and enforcement of agencies’ practices in this area. Abuse of the standard placement fee contributes to debt bondage, which is significant given that some are forced to sell their meager assets or secure high interest loans while others accrue this debt directly to the recruiting agency.

- Consider means to reduce debt bondage. The issue of debt bondage is paramount as in many instances, it is an employee’s debt that triggers their entrapment in exploitative and abusive employment. Systemic labour migration costs associated with training, recruitment and placement fees could be offset by government, or minimized through the provision of no-interest government loans.

- That mandatory testing for HIV should not be required for migrant workers by the

imposed on migrant workers as a pre-condition of employment. Rather,

following a right-based approach, migrant workers should be provided

Policies and procedures for protection for migrant workers overseas

Embassies should play a more effective and central role in advocating for the protection of our migrant workers’ rights and helping migrants who need assistance.

Protection of the rights of migrant workers is a core part of their duties and regular work -- and they should be held accountable if they fail to provide effective assistance migrant workers in need of help.

Government should insist that migrant workers shall not be discriminated against in any way. The Government should also insist and actively work to ensure that all migrant workers are treated equally before the law in receiving countries.

Training, Safe Migration and Awareness Raising for Migrant Workers

The new training program should use a rights-based perspective to educate migrant workers, thereby helping to empower them and promote their ability to understand and take actions to effectively protect their rights.

We believe that safe migration approaches offer important information and understanding to intending migrant workers which can help them protect themselves when they depart the country to work. Therefore, safe migration principles should be taught to migrant workers, and should be combined with practical information (tailored to the situation in the country to which the migrant is going) as part of the pre-departure curriculum.

Safe migration information should also be widely disseminated to the communities where migrant workers originate.

The Government should establish a program of awareness raising for migrant workers about all the relevant details and risks of working outside of the country and ensure that this information is spread in communities where migrant workers originate, and re-emphasized.

Policies and procedures for protection of domestic workers

Pass the Batas Kasambahay Act. This will give domestic workers greater opportunity to access basic labour rights and entitlements and reduce the risk of their abuse and exploitation.

Prosecute employers who abuse workers, including confining domestic workers to the workplace. Greater attention needs to be paid to the investigation and prosecution of Filipino employers who abuse workers. Cases of psychological, physical and sexual abuse, food deprivation, and forced confinement must be pursued.

Trafficking in Persons

First and foremost, Government must ensure that all its officials, both inside and those working at Embassies overseas, fully understand that human trafficking is a crime that is committed against all persons – women, children, and men – and for all end purposes, including trafficking into forced labour. The Government should actively promote this understanding in its engagement with other Governments in ASEAN.

NGOs and other stakeholders to monitor the implementation of the law and make public reports and interventions when cases of abuses occur.

The Government should find resources and make arrangements to provide proper training on basic knowledge on human trafficking to police authorities, with a special focus in assisting police be able to effectively identify victims of trafficking. Police reforms should also be considered, such as formation of a truly independent, professional, and non-corrupt police authority at the airports and seaports to improve anti-trafficking response.

The Government should ensure that there is effective legal protection for victims of human trafficking. The Government should take all steps required to ensure that persons who are victims of human trafficking are not held responsible for criminal offenses that they are forced or coerced to commit while being held in trafficking situation. The Government should also insist on such protections for its citizens who are trafficked overseas and make bilateral representations to all Governments inside and outside of ASEAN which do not abide by this core international standard practice.

We urge the Philippine government to re-open the “runaway “ shelter in Jordan which was closed by the Philippine embassy just last June. Abused and exploited migrants and trafficked persons overseas should be provided with an appropriate place/center to guarantee their personal safety.

Increase efforts to identify and prosecute cases of official corruption. The Government should increase efforts to prosecute cases of official corruption. Many reports cite the issue of official corruption as a major factor undermining the government’s detailed labour migration structure. Increased policing and prosecution is required to enable the official structure to operate effectively.

We urge the various Philippine government agencies and the anti-trafficking mechanism established i.e. the IACAT, to study the findings on the human rights impact of anti-trafficking measures and consider the ten recommendations of the GAATW research report “Collateral Damage”. We wish to highlight four of these recommendations that we think should be a priority:

- Give trafficked persons better access to justice and compensation.

- End the practice of making assistance conditional.

- Create more safe opportunities for migrant workers.

- Ensure decent working conditions for all workers

Recommendations to ASEAN

We strongly believe that the regional Instrument on the Protection and Promotion of the Rights of Migrant Workers (which will be developed by the ASEAN Committee to Implement the ASEAN Declaration on the Promotion and Protection of the Rights of Migrant Workers) should be legally binding on all ten ASEAN states.

We recommend that the Government should conclude bilateral MOUs/agreements (with focal points established to ensure effective implementation of the agreement) with key nations. These bilateral MOUs/agreements should be in accordance with the principles and provisions of the above-mentioned regional agreement, and should be understood to supplement the regional agreement and to address bilateral issues that are outside the scope of the regional agreement. It must be clear that the bilateral MOUs/agreements of any sort must be in accordance with international human rights and labor standards.

We recommend that there should be an agreement on a “standard medical package” of services that will provided by receiving states (in cooperation with sending states) to migrant workers wherever they are in ASEAN. The provisions of this package would have to be negotiated, but it should contain elements of preventative as well as curative care, access to public hospitals, reproductive health and family planning, and public health and hygiene information. A core element of the plan would be a requirement for the employers of the migrant workers to pay costs associated with the medical package, and a strict prohibition against employers making deductions from migrant workers’ pay for medical costs.

All ASEAN nations must adopt regulations that permit documented migrant workers to change employers without losing their work permit status or their right to continue to work and reside in the receiving country. These regulations should neither be burdensome nor should they require any additional expenditure by the migrant worker to change the employer listed on the work permit.

There must be a clear and absolute prohibition on seizure of passports or migrant workers’ documents, or the destruction of those documents, by Government officials, employers, brokers, agents, recruitment agencies, or any other persons in the receiving country. There should be severe penalties imposed against persons who seize and/or destroy migrant workers’ documents.

In accordance with international core labour standards, the Convention on Migrant Workers (CMW) and other international human rights instruments, all ASEAN states should allow for migrant workers to form and/or join trade unions in the receiving nation.

No ASEAN country should criminalize undocumented migrant workers nor use corporeal punishment (such as caning) against migrant workers.

ASEAN should set out a no-tolerance policy towards use of violence against migrant workers, and should ensure that all its member nations provide migrant workers with the same rights to access to justice as the national of the receiving country. Migrant workers who return to their country of origin shall have the right to file a legal complaint against an abuser in the receiving country. A system (if not yet in place) should be developed where the migrant worker can file a legal complaint through the Embassy of the receiving country, and this Embassy would then be required to transmit the complaint back to the receiving country for action by the receiving country’s courts. The Philippine embassy in the receiving country should be required to monitor the progress of the migrant worker’s case filed in the receiving country’s court, and provide regular updates.